This lesson is about adding variety to your color schemes.

You have two choices with this lesson, watch me discuss the issue in

the video below, or read the full text.

I can't take credit for the first version of this lesson, it was

first taught to me at age 6 when I attended art classes with

Canadian Wildlife painter

Renate

Heidersdorf. I was very lucky to get a place in one of her

afterschool classes, and I thank her for this invaluable lesson that I

still use today.

Every year in the fall, classes started out with us doing a nature

painting. When I was like 7 or 8, we did the following, first, open

the ink that was called "Green". Place it on the paper. Observe the

color. Probably medium brightness, not quite neon, but very generic.

Then in the next 20 minutes we had to mix on the paper 20 different

greens.

Green with yellow mixed in. Green with blue. Green with brown. Dark

greens,

light greens, Lime greens. As many different greens as we could make.

The purpose of the exercise was to realize that just because this ink was called "green" does not mean it should be used to paint anything we know to be "green".

Once we finished this exercise, we then painted a nature scene of some sort. And of course, we were expected to use lots of different greens, different greens for different trees, grass and plants.

The Rules

Now, it may seem odd to have small children follow a rule like this,

"No premade green is allowed in your painting". But in fact, it is not

a rule as much as a method of breaking the rules. When we are small and

are holding our first crayon, we have total freedom. If we want to make

the sky green, we can make the sky green. I mean, why not, if that's

how

our minds saw the sky. But soon afterwards, we start looking to our

parents

for answers to our questions. Such as, "what color is that tree?'

"Well,

it's green". "What color is that grass?" "It's green." "What color is

that

car?" "It's green". Pretty soon, we have all the answers we need, all

of

these things are now categorized, they are all green. So no wonder when

a person starts making artwork, they immediately reach for that generic

green

for the grass and trees. After all, they're all green, this

crayon says green, so I should make them green.

This is the difference between painting what you see and what you know. In the book "Mass" by John Harris, he explains how he had a teacher who was convinced that is was more important to paint what you saw then what you knew. As in, forget that you know what that object is, paint the lights, paint the darks, paint the color, paint the shapes, and eventually the object will just take care of itself. Try this as an exercise sometime, find something and try painting what you actually see vs what you know the object looks like. Your observation skills will multiply in no time. And all of a sudden you see how the object really looks outside of what we expect it to look like.

The Natural WorldLets take a few shots of the natural world. Here's a patch of ivy, notice the huge variety of greens, some leaves are light, some are dark. Some are in shadow...

Even upon close inspection, the leaves themselves are different colors, with veins and spots and other detail, many, many different greens.

And here's a lovely garden scene, plenty of different greens there,

I've picked a few of the colors and placed them on the right side for

you with Photoshop's color picker.

Lets Make Some Grass

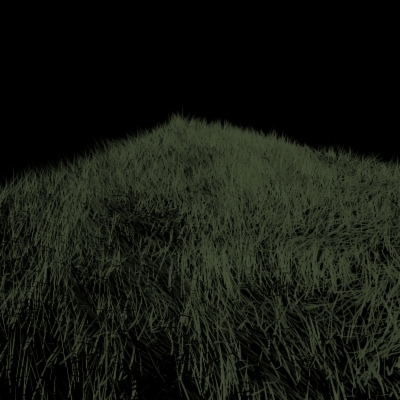

Following these ideas, lets make some grass. Below is a picture of some simple 3D grass, with a generic green color. Ok, looks good, but there's something missing. The eye sorta gets lost in the grass, since it's all the same bland color.

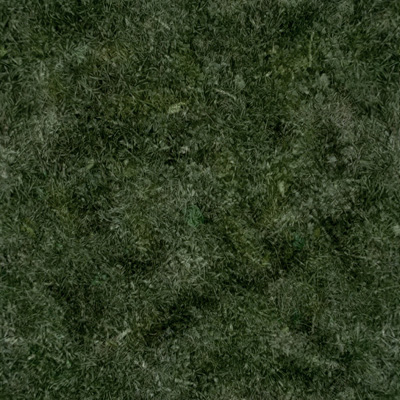

Here's some real grass, notice the variety in greens...

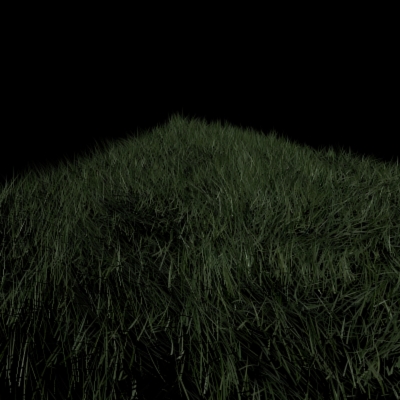

So let's add some greens variety. Thankfully, I can apply a bitmap to this 3D grass to specify the color of the blades of grass. Here's a bitmap, imagine this projected from above the grass. When a blade of grass grows, it chooses it's color based on the color of this image at the position the grass is growing. So if it grows from a pixel that's black, the grass itself will be black at that point.

And here's the map applied to the grass. Notice how this adds variety and ends up being more pleasing to the eye, as well as more realistic.

Conclusion

So next time you are painting a painting or texturing a 3d scene,

don't pull out that single color crayon. Make sure to add variety to

the colors, the results will be more believable and visually

interesting.